Ancient Longings

“Theoretically, a perfect photograph is absolutely inexhaustible. In a painting you can find nothing which the artist has not seen before you; but in a perfect photograph there will be as many beauties lurking, unobserved, as there are flowers that blush unseen in forests and meadow ….

Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mold on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it ….

From an essay concerning photo-aesthetics by 19th Century American physician Oliver W. Holmes. Published in Atlantic Monthly (1859)

Some necessary acknowledgments:

Thanks to Oliver Wendell Holmes (father of Supreme Court Justice Oliver Holmes Jr.); and thanks are due Lucretius, First Century B.C. Roman poet/philosopher who fed the mind of Holmes Senior — a sage in his own right and also, it appears, a Nostradamus figure. Consider what Mr. Holmes wrote in another passage from the same essay:

There is one Colosseum or Pantheon: but how many millions of potential negatives have they shed — representatives of billions of pictures — since they were erected. Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble our selves with the core.

Doctor Holmes seems to have foreseen digital photography habits in the 21st Century. He believed objects and configurations of objects shed facsimiles of themselves, negatives made positive in the perceptions of living beings. The wafer-thin films contemplated in his philosophy continually flake off the surface of things. Notice the exaltation of the photographic process: camera operators capture the very fruit of creation, instantaneously carrying away the precious form, leaving the material entity (or the mold) behind and forgotten.

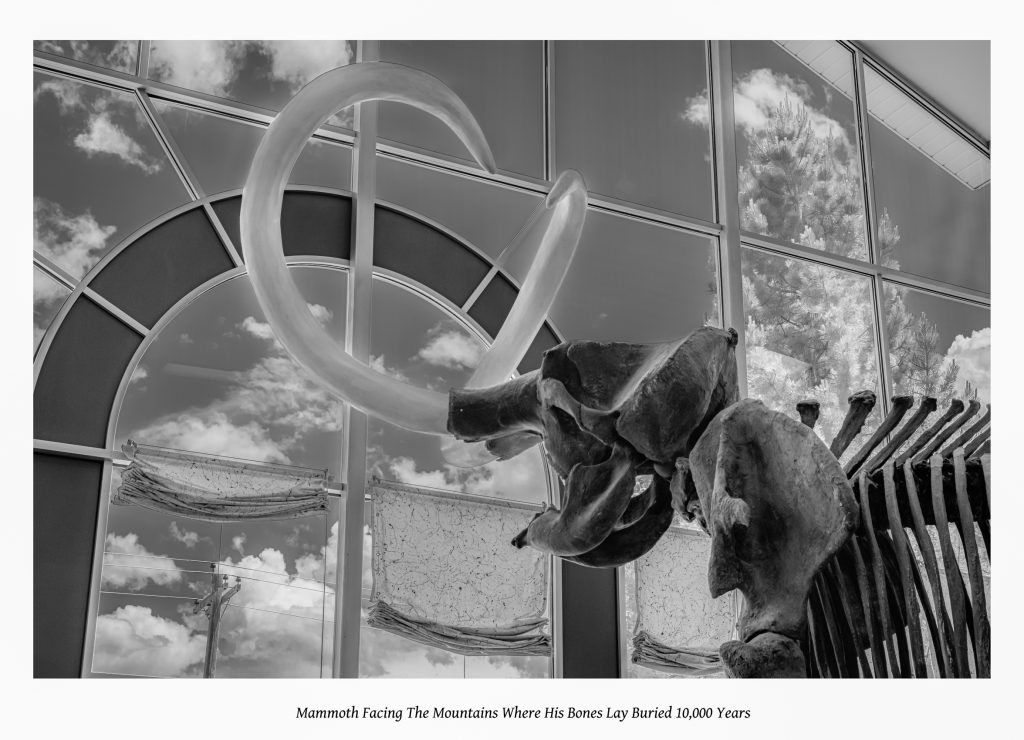

Beyond question photographers have grave dependencies. We are symbiotically (and in a sense: parasitically) related to the labors of other human beings, and beholden to the creative power and intelligence of the universe in a big way. We seek out and frame, highlight and embellish the products of other artists and craftspeople. In this picture I lean on architects, exhibition curators, paleontologists and textile designers, to mention just a few entries on what could become an exhausting list of expertise. Together these workers provide the reconstructed form of an extinct animal — artfully positioned — curtains in an abstract-expressionist motif, and arched, soaring, irregularly-shaped windows whose arrangement makes possible a vision of mountains and dramatic skies. We should give credit to the guys who set that utility pole and strung the wire in the left-hand corner of our image. Their efforts anchor us. Without this artifact I fear we would be adrift, untethered from the continuum of time.

Assuming it sends a meaningful signal, how shall we read this photograph — is there significance to be found?

Does beauty lurk unobserved here — are there flowers that blush unseen?

The image engenders (at least in me) strangely intense empathetic feelings, a sense of loss and longing, an identification with our subject. This re-assembled tusker no doubt represents one of the last of his species to walk the Earth; woolly mammoths have vanished, remaindering only genetic information and fossil skeletons. This realization in itself provokes mournful emotions. Qualified experts speculate our ancient pachyderm behaved socially like modern African elephants, with similar intelligence and developed consciousness. In that case, the mammoths would have formed strong emotional bonds with their kin, and did have the ability to form long-held, highly-accurate memories.

Our motif contains a detail which acquires meaning when viewing the image as a whole; notice the jaw-bones attached under the skull of this specimen. Observe how this deeply-carved mandible suggests the flexion of muscles and ligaments. From our angle of view, appendages seem to reach forward from these bones in a posture of prayer and supplication. The tilting upward of the elephant’s head points his eye-sockets directly at high mountain ridges, over the horizon of which his bones waited a hundred centuries to be resurrected.